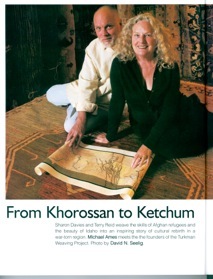

The Anatomy of a Good Rug: From Khorossan to Ketchum

Sharon Davies and Terry Reid, founders of the Turkman Weaving Project, weave the skills of Afghan refugees and the beauty of Idaho into an inspiring story of cultural rebirth in a war-torn region.

Terry Reid and Sharon Davies have traveled so extensively, to such remote, dangerous corners of the globe, some have wondered if they aren’t secret agents. On these trips, the couple has had some close calls, but also stumbled upon vital sources for their business importing fine central Asian art, antiques and rugs. The Turkman Weaving Project was born on one of these trips in the early ‘90s. Fifteen years since its humble start, the project has evolved into a thriving cross-cultural exchange, bridging the vast gap between Idaho and the mountains of Central Asia.

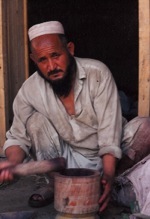

Traveling through the refugee cities of western Pakistan in the early ‘90s, Reid encountered scores of Turkman Afghans who had fled the soviet war in their own country. Displaced and unemployed, the refugees possessed an untapped wealth of tribal art skills. In their poverty, the weavers struggled to produce even cheap rugs from low-grade synthetic materials. Without organization, the secrets of their ancient craft appeared doomed to die with tribal elders.

Reid, sensing an opportunity both for the refugees and his own business, stepped in. He set up shop in the corner of a dusty rickshaw parking lot, encouraging the destitute workers to create tribal rugs he could sell in America. Within a decade, this vision has evolved into a very real means of income and education for upwards of 100 Afghans and their families in the refugee camp of Khorossan, just outside the teeming city of Peshawar.

By their own proud admission, Reid and Davies have always been hippies. When they first met in the mid-1970s, these Boise natives weren’t kids just refusing to let go of the fads of the ‘60s; they were true sell-everything-but-the-clothes-on-your-back-and-travel-across-the-world-hippies.

Whether or not they deserved to retain that label today depends on how you reconcile the stereotype with the accomplishments of their life since embarking on their astounding and exotic journey.

When the Turkman Weaving Project began, it was not exactly an idle gold mine waiting to be pounced upon by the importer. Through intense collaboration with workers and Mohammed Kamil, their on-site manager and friend in Pakistan, Davies and Reid built a bustling trade channel from scratch. Industrial carpet making, with its synthetic dyes and flimsy fibers, has leached the culture of proficiency and weaving skills, so Reid began by revitalizing the very basic raw materials: dyes and wool.

“I walked into Kamil’s house one day,” recalls Reid “and I looked at what they were making and I said ‘You guys aren’t going to make it.’” Reid told Kamil to start buying natural, vegetable dyes and to relearn the ancient methods. Kamil began purchasing high-mountain, hand-spun wools from Afghan Muldaris, a nomadic Pashtun tribe. His weavers rediscovered traditional dyeing agents; pomegranate rinds, walnut husks, madder root, berries, bark and insect scales. This insistence on natural ingredients was no mere back-to-the-land hippie sentiment: it is common practice among Oriental rug experts. Nearly a century ago, in her book “Rugs in Their Native Land,” E.D. Norton made no equivocations: “Vegetable dyes are the ‘sine qua non’ in a rug,” she wrote. “All other dyes will disappear or change (over time).”

Twenty-three years since opening the first Davies-Reid Gallery in Boise, the couple has forged something of a central Asian imports empire. From their base in Ketchum, their influence radiates outward – like so much good Karma – to galleries in Wyoming, Boise [Utah] and Maui. Calling them “galleries”, though, is a bit of a misnomer. One doesn’t go just to look, but instead to hold, touch and turn exotic objects in the light. The stores are aesthetic pleasure dens, brimming with antiques, collectibles, peasant art, jewelry, scents and mountains of handwoven rugs.

It’s not much of stretch to say that Davies and Reid have made a career by selling whatever they could bring home from far-flung trips. The sprawling Ketchum store retains that organic and informal vibe of an eccentric traveler’s grandiose souvenir collection. Davies-Reid is like a scrapbook, manifested in literally tons of goods.

Despite the spoils, the couple is far from jaded. “To come from Boise, I had never seen an Oriental rug as a child,” Reid said. “To come to understanding and creating a business in that part of the world, we have been incredibly fortunate. And part of that success is that it needed to happen. These people really, really needed work and help.” Reid is convinced that, for millions, of tribal people throughout the world, free trade of traditional crafts is the ticket out of poverty. He makes a distinction, though, between deeply rooted cultural arts like rug-making and cheap sales of ethnographic trinkets.

“You have to transcend tourist souvenir art – you take indigenous skills and put them into goods that Americans and Europeans will buy for their houses. It’s not this cute little tribal thing anymore; it’s the skill behind it that counts.” At the risk of sounding “so George Bush,” said Davies, Reid calls the vision “compassionate capitalism.” They believe in the transformative power of globalization and trade. “What people need around the world is work, more than anything.”

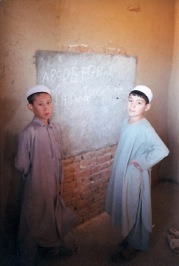

Once the weaving project outgrew the Khorossan parking lot, Reid built an open-air karkhana (factory) on the outskirts of town. “It looks like something from the American Southwest, circa 1900.” High adobe walls and verandas were built to accommodate looms large enough to create rugs upwards of 375 square feet. (A team of weavers can complete about six centimeters a day; even working every day, a big rug is a four-month project.) With the infrastructure in place, Reid set out the beautify the site. He planted pomegranate and grape trees – the fruits are used in dyes – and a Tandoor oven to feed dozens of workers. The karkhana is now an open and peaceful oasis in a region of overcrowded and miserable refugee cities. In nearby factories, where 11-year-old children work 14-hour days, such attention to creature comforts in unheard of. Reid’s workers often earn three times the average local wage and today, many send their children to schools built with weaving-project funds.

As the project hummed along, Davies and Reid continued their own nomadic ways, shuttling between Boise and Ketchum. They were driving through the Camas Prarie’s quintessential western American landscape, when yet another idea struck.

As the sage greens and bleached siennas streamed by the car windows, the inspiration for a new series of rugs based on the Camas Prairie took hold; the colors of Idaho woven into Afghan tribal rugs. They sent photographs to Khorossan of autumn hikes, of the desert sun illuminating sage-covered hills and light ochre rocks. The weavers began to produce Camas rugs, and a tribal art crossed the cultural divide. In color and design, the rugs are often reminiscent of Native American weavings.

Rather than viewing the series as bridging gaps, Reid believes it is more natural to think of the Camas rugs as completing an epic circle of global interconnectedness. His theory begins with ancient Oriental rugs, some of the earliest textiles ever made (circa 500 B.C.), whose designs traveled the caravan routes from Asia into Europe and, with Islam’s Moorish influence, into Spain. When the art became further disseminated through Spanish conquests in the New World, Native American cultures reincarnated them yet again. Typical Navajo designs, then, may have their seminal routes in the high steppes of Mongolia. How else could rugs so fit for an Idaho have come so naturally from the hands of Afghan weavers? The theory is not an easy one to prove, but when sitting in Ketchum on a deep pile of Camas inspired rugs woven in Pakistan by Afghan refugees, the circular nature of civilization is hard to deny.

Walking barefoot atop what seems like acres of rugs in their Ketchum store, Davies and Reid set a tone of easy sophistication. Their First Avenue store is the kind of magical playground where children willfully get lost. People tell Davies that they come in just to wander and use the aromatic and exotic space as a meditation retreat. Standing somewhere between the vials of liquid frankincense and the woven salt bags of the Himalayan steppes, one can peer down between the stairs and, catching a glimpse of those great piles of rugs, remember this is Idaho.